The Search for My Lestat

Thoughts on the Nature of Book to Screen Adaptations via the Vampire Chronicles

One thing about me is that, if good fortune or insanity ever led me to go back to graduate school again, it will be for a PhD in Film Studies with a focus on adaptational studies. I was a little kid who cared about media a lot, and when I was nine two of my favorite books got giant adaptations that were released over multiple years and became massive cultural properties. For a kid who was really interested in not just the media she liked, but why she liked it, adaptations became a lifelong fascination for me.

Another thing about me is that I love watching people arguing with each other on the internet with a big bowl of popcorn, so this combined with my love of adaptations means I see a lot of conversations when a beloved book is becoming a movie that I often find frustrating. People tend to talk about book to screen adaptations as though they are a graded test you can score, but the nature of what makes an adaptation “good” is intensely complicated. I may not be a PhD yet, but I am an armchair lover of studying internet arguments and adaptations, so I have some pretty defined feelings on what makes a good adaptation and what makes a bad one, and I think even if you don’t have the same taste as I do, you may find value in using some of the tools I use when thinking about media adaptations to understand your own opinions.

The current creative work that is consuming my soul is the Vampire Chronicles by Anne Rice, which just so happen to have been adapted into several different mediums over the course of the last thirty years, and having recently watched or re-watched a lot of them as part of my love affair with the book series, they're going to be most of my examples here. I'm going to have my own subjective opinions, but what I want to talk about is the standards on which people base their opinions of adaptations as being "bad" or "good," not the merit of those opinions themselves, which I hope I'll be able to explain and which I hope you will find value in.

Part 1: Why The Movie Isn’t Like the Book

Any adaptation of a story between one medium and another is going to change the way the story is told, because every medium has different basic strengths and weaknesses based on its form. For example, movies have a lot more tools to create suspense as a physical reaction in people than books do, because they are multisensory and the time period in which they are consumed is mostly within the control of the filmmaker. A scene in a horror movie has music, sound effects, spoken word, and visuals to create the effect the filmmaker wants it to have on you, and generally in a movie they expect that you will watch it at the speed they intended, in the order they intended, and in one sitting. A horror television show has the same features, but when it first airs it also in some circumstances has even more control over the temporal experience of the audience: the episode just ended with a shadow falling over the character and a scream, wait until next week to find out what happens next!

Books are not multisensory (other than the physical sensation of holding a book, and I'm sure a horror author has used that in the past at some point) and importantly, the temporal experience of reading is not within the author's control. As a reader, you can pick up a book, read ten pages, put it down, leave off on a chapter break or in the middle of a random sentence, you may be a fast reader who is immersed and reads it over the course of an evening, you might be a slow reader who reads ten pages a night, forgets the book on a business trip, and picks it back up two months later. The tools that horror has in the context of film or television to create suspense and tension are not tools that the author of a novel has access to, but horror is still a popular genre in both mediums.

What a horror author fundamentally uses to create the experience of what makes a good horror novel are the strengths of the novel medium. The novel has more control over the reader's experience of the characters' internality, it can use the tone and the writing style of the narration to set an uneasy mood or a comfortable one they can shatter, they can use the tools of different genres to mislead the reader, they can chose how much space to spend describing things and extend a millisecond forever or use a brief description skip ahead and create dramatic tension. Even in the realm of visuals, where the novel might be at a disadvantage to film, a good horror writer can turn that into a strength. As a person who likes horror novels and not horror movies, I can personally say that no filmmaker will ever make an image as terrifying as the one I can make in my own imagination.

In the book Interview with the Vampire, the opening scene is the same as the one in the 1994 movie, where the existence of vampires is revealed to the interviewer before the interview starts. In the book, the only thing the vampire has to do to remove any doubt that he is a supernatural creature is turn on the light; his appearance is so unnatural, so otherworldly, so impossible, that seeing him in direct lighting is all the boy needs to understand that his claim that he is a vampire is true. This cannot translate to film, both because you need the character to be portrayed by a human actor, and because the type of visual that would be so immediately terrifying that it would instantly make you believe in vampires is going to potentially alienate viewers early in the story if they find it either too off putting or not believably unnatural enough. The idea does not translate, and so the adaptations of the scene in the television and movie adaptations both substitute it with the vampire demonstrating superspeed, because they need something that can work in the medium of film to convey the same idea.

When a movie doesn't include all scenes from a book, often there are a lot of assumptions about the reason why. This star wanted more screentime, they couldn’t afford it, or audiences just aren't smart enough to understand literature (which is my personal favorite), but any book that becomes a movie is going to have to fundamentally change, because you cannot create the experience of reading a book within the experience of watching a movie. Movies are not books. You could have infinite money, time, resources, and technology, and you will never translate the exact experience of what reading a book is like to film.

A big part of this is also because, when you are reading a book, you are in many ways an active creative participant in the storytelling experience for yourself. Think of a time when someone said to you, "well, that's not what I imagined that character would look like," as a reason why they think a casting decision was a bad one. To me at least, more so than in the medium of film, books require the reader to engage on some level with their own imagination. You're never going to translate a book directly into a movie, because there is no way you will also translate the individual creative engagement of every reader into a medium like film where many of those individual choices have to be more concrete. That character's actor is going to have to be blond, or brunette, and if the book doesn't say one or the other, at least one reader is going to decide that you chose wrong.

Obviously, if we want to talk about Interview with the Vampire's adaptations, choices had to be made for practicality, but also a lot of concrete choices had to be made because of the mediums of film and television that never needed to be made in the book. Claudia was not going to be played by a five year old human being in any adaptation because of things like child labor laws in the film industry and a factor I'll call "basic human morality," but anything that was not absolutely concrete in the novel that has to be concrete in a visual medium had to be a subjective choice by the creative team.

Do the vampire's fangs in the Vampire Chronicles retract when they are not biting people, or are they always out? I am genuinely not sure, and I just read a ton of those books. As a reader, I assume they do retract, but I could see a reader assume that they don't, or I could have just missed a clarification about whether or not they do. Because I think they do retract, to me, in the 1994 film adaptation, the fangs are wrong, because they always have them. To a reader who imagines they are always out, the 2022 AMC television adaptation would be wrong. Both adaptations had to at one point decide which they were going to go with, and whether because of their own interpretation of the books or their priorities from a practical standpoint, they decided on one the other adaptation did not.

Changes must happen because the medium of the novel and the medium of the film are working with different toolboxes.

Part 2: Getting Some Practical Matters Out of the Way

I want to quickly get the practical factor out of the way before we move forward: even though things will obviously have to change inherently in any word to screen adaptation, some changes are just because movies are big complicated operations where small choices can be the difference between a three year long filming schedule that costs half a billion dollars, and a movie that actually gets made. As much as I have other issues with the 2002 movie Queen of the Damned, which I will come back to later, even if a page by page adaptation of the book The Queen of the Damned would have been coherent and enjoyable to watch, which it wouldn’t have been, it would have probably also cost an absurd amount of money. We live in a material world where stuff costs money, and so I will not pretend that sometimes, the choice was made to change something because if that change hadn't happened, the movie would have been impossible to make.

There are also changes that are made because of things outside of anyone's control, because we live in a world where things like human age exist and sometimes appear on film. I already mentioned Claudia, but also the ages of characters tend to shift in adaptations because how accurate to the source material an actor's age is is usually a lower priority than the quality of the actor's performance. Some properties, like ones with vampires in them, also have to work with the reality that in season ten of your vampire show, your immortal vampire who is "forever physically seventeen" is going to be looking really eligible to run for the United States Senate, so you may save yourself a headache by adjusting the age of the character to allow the actor to work better with the role over time.

I may love my forever teenage gremlin Armand from the books, but I'd much prefer my forever twenty-seven-year-old Armand and ten seasons of AMC's Interview with the Vampire.

Part Three: How Do Good Adaptations Make Choices About What to Change?

Once we accept that part of the original work is going to have to change, what types of changes are the ones that separate a good adaptation from a bad one? What changes are just enough? What changes are a bridge too far? And is an adaptation good if all it does is make the minimum number of changes in translation?

I'm going to say the answer to the last question above is definitively no. A good adaptation of a book or another work must be, on some level, a good work in its own right. A faithful adaptation that changes as little as possible and works as a film without being particularly good can be fine, but a really good adaptation of a book to the screen will be a good film or television show as well, because the purpose of adapting a work from one medium to another is to create two complete creative works that function successfully. Lestat the Musical, as it first appeared in San Francisco, is a surprisingly faithful adaptation of the books Interview with the Vampire and The Vampire Lestat but does not inherently function well as a work of musical theater. Most of the important scenes and characters from both books are present, much of the dialogue is directly from the page, the things that are cut seem reasonable to fit the story into the runtime, but also it is completely impossible to follow as a story and also the songs are bad. They did not change the source material in a way that allowed them to make a coherent stage musical, and so even though it includes so many specific elements from the books, it is a bad adaptation. Also, I already mentioned, but will repeat: the songs are also bad, and for a musical to be a successful work, the songs kind of have to be good.

Because the priority in adapting a book to screen must also be to create a quality movie or television show, the question of what is going to change is interrogating the text from the wrong perspective. The question is not what is going to change, the question is, what is going to be translated? What quality of the original work is worth translating into another medium? What is "good" about the book that will also be "good" in the adaptation, and create a successful work containing that quality? What choices, based on the change in medium, need to be made to translate that quality?

Obviously, what each person likes about a particular book is subjective, but usually good adaptations are able to find multiple features of the original work that are the core of its appeal to carry into another medium. Some aren't going to feel optional at all: you probably can't make a movie called Interview with the Vampire and not put a vampire in it, but some elements of a story that feel fundamental to a large number of readers may require significant other changes to be successfully translated.

What, in the original source material, made it "good"? Why do readers enjoy reading the Vampire Chronicles? What are the elements of the books that make readers cry, laugh, get excited to start the next chapter, continue the series, and call it their favorite? What, in abstract pieces, makes the Vampire Chronicles the Vampire Chronicles?

Everyone will have their own personal answers, but to me, it's the philosophical discussions, the themes around the search for morality and purpose, the well-defined characters and their dynamics with each other, the historical fiction elements and the scope of the timeline, the haunting and evocative horror scenes, the touches of black humor and absurdism, and the extremely distinctive lush gothic mood in the writing style. You can translate any of these to an audiovisual medium: you cannot translate all of them at once and make anything even slightly functional as a movie or television show. You must choose which will fall by the wayside, and which will be prioritized as a guiding principle that dictates what else will change.

Neil Jordan's 1994 film Interview with the Vampire, which had a screenplay written by Anne Rice, manages to spin a huge number of plates, but does have clear priorities. If I had to pick one, I would say the guiding principle of this adaptation is the atmosphere and general mood of the book. A lot of the original dialogue and its associated style makes its way into the story, the visual style and music are romantic and melancholy, and the emotions of the characters are always front and center. The events of the story and the tone of the story go well together, so on a scene-by-scene basis the changes are not particularly dramatic. What is less prioritized, by necessity, is the direct adaptation of the particulars of the dynamics between the characters. Lestat is a bit smarter than he is in the first book, Claudia is a bit more expressive, Brad Pitt is asleep (but also Louis is less petty). A lot of these are required changes to maintain the atmosphere in the film: if Lestat is smarter we don't have to step away from the sense of wonder and dawning horror that Louis has about his life as a vampire to get into constant arguments about money and Lestat's dad, Claudia being more expressive makes the tragedy of her story more available to us, and Louis and Armand are a bit less gay out loud so that a movie this Gothically romantic can exist in 1994. If you like the tone, the themes, the setting, the dialogue, or the numerous arsons in the book, all of that is there for you in the movie, and those are the things that appeal to a lot of readers who love Interview with the Vampire.

But what if, when it comes to the Vampire Chronicles, the characters are the most essential element of why you enjoy them? It's a great film, it's a faithful adaptation, but no adaptation will ever be perfect for every single person. A reader who can appreciate a lush writing style but is there mostly for the characters can appreciate that the movie is good, but for that person, it won't have captured what they personally found appealing about the source material. If the beautiful part of the themes of the story are how they play out in the dynamics between the characters and not in specific spoken dialogue, the themes will feel a bit less correctly adapted. A reader will have their own emotional interaction with a story the same way a reader will have their own creative interaction with a novel, and an adaption will also on some level be making a choice about what kinds of emotional interaction with the work they've decided to prioritize in their adaptation.

For Vampire Chronicles readers who rank Interview with the Vampire higher on their ranking of the books in the series, I'd imagine the 1994 movie is a near perfect adaptation. The biggest strengths of that novel are translated into the biggest strengths of that film, and the parts less prioritized are also not usually what is cited as the primary appeal of that specific book. For Vampire Chronicles readers who rank other books higher on their personal ranking, the elements of the story that are less prioritized may be more core to their enjoyment of the series, so the adaptation will feel less successful. My personal emotional interaction with the Vampire Chronicles as a whole is largely tied to how the themes and philosophies of the series play out through the specific personalities and interactions between the characters, and so, though I can appreciate how good an adaptation of the book it is and how fantastic of a performance he gives, Tom Cruise is not my Lestat. I do not have the same emotional interaction with him as a character as I do with the one in the book.

Part 4: What Happens When the Adaptation Makes the Wrong Choices?

Interview with the Vampire, the movie, is a good adaptation of the book regardless of how it doesn't hit the bullseye for me, personally. It is a good adaptation. It set specific goals, met them, and those goals were directly based on the substance and the appeal of the source material. That is what a good adaptation is.

So, what's a bad adaptation?

Good adaptations do not need to pander to actual fans of the original source material, but a successful adaptation, as stated previously, adapts the appeal of the original to someone, and preferably, to a reasonable number of people who liked it. Someone's favorite book is Memnoch the Devil because they were struck by lightning outside of a church and the paper it’s printed on is their favorite food, but in the broad strokes there will be central appeals to a story that are what make it interesting to people in general. If the book is good enough to adapt for some reason, that reason is also probably good enough to be a factor in how you adapt it. When you adapt a book, something central about why you adapt that book should probably be related to that book.

I would not say that the fact that a vampire at some point joins a rock band and kisses a lady are the central appeals of the books The Vampire Lestat and The Queen of the Damned for me, personally, or for most people who would willingly read the thousand pages of which they are comprised.

If I had to separate bad adaptations into two categories, the ones I have the most sympathy for are the ones that either did not successfully manage to adapt the core element of the original story they were attempting to adapt, or who simply did not chose a core element that was related to the appeal of the original to most readers. To step away from vampires for a moment, I am a massive fan of the book The Disaster Artist by Greg Sestero, which was adapted into a film of the same name. Most people who haven't read the book think the movie is fine, but I and a lot of other fans of the book were disappointed central reason the filmmaker chose to adapt was the behind-the-scenes glimpses in the novel into the making of the notorious bad movie The Room. For me, the core appeal of the book is how it manages to tell this very surreal story in a way that feels very grounded in the coming of age of the protagonist of the memoir, and how it uses this bizarre success story to make comments about the nature of the American Dream. Yes, I believe we do learn in the movie that a character in The Room is named Mark because Tommy Wiseau thinks Matt Damon's name is Mark Damon, but in the book, it's both funnier and more impactful because of what it actually reveals about Tommy and Greg’s relationship. The filmmaker identified the elements of the book that translated to a workable comedy film but missed the mark for those who enjoy the book because the elements that translate to a comedy film are not specific to the book's appeal.

In the other category, we have adaptations that chose the guiding principle of their adaptation because that feature is something marketable or desirable, and do not pay particular mind to whether or not the things they are choosing to adapt from the original story are part of what people find appealing about the original. For example, I am a huge fan of the book The Hobbit, because it is a fun adventure story for children that takes place in a fully realized world. The appealing elements of the novel The Hobbit to its fans are simple, which is why choosing to prioritize the few minor action scenes in the book above everything else when you adapt it is confusing. Why are you adapting The Hobbit if you seem to not like the book The Hobbit? I know the answer is because the studio wants another Lord of the Rings property, but the elements of the story that the movies prioritize because of that external motivator make them a terrible adaptation of The Hobbit. The tone is all over the place, the character arcs don't make any sense, the scope of the story is bizarre, and all of it is because you cannot shape the core elements of the story of The Hobbit into a Lord of the Rings shaped movie. It doesn't work as an adaptation, and in being a bad adaptation, it is also a bad series of films.

The 2002 movie Queen of the Damned I would put definitively in the latter category, where the guiding principle of the adaptation is not based on the core appeal of the original work from anyone's perspective but is based on an external element that originates from a separate motivation. Queen of the Damned was made into a movie not because somebody wanted to adapt the novel The Queen of the Damned, but because a movie studio wanted a vampire property that was appealing to teenagers to play off the success of other recent franchises. Every decision made in adapting the book The Queen of the Damned into the film Queen of the Damned is based on the guiding principle of trying to fit the elements of that book with any changes necessary into the shape of a specific genre of crowd-pleasing action movie.

To be clear, a second external motivation does not always result in a bad work, even if that work is not a good adaptation of what it's based on. Often a second external motivation can either complicate a story that needs complication, or par down the more controversial elements of a story to something that is more broadly appealing and works better as a cohesive narrative. Some examples I'd say fall into this category are Stanley Kubrick's movie The Shining, which does not particularly adapt the themes or story of the original novel, and the Broadway musical Wicked, which to my understanding uses the extremely basic premise of the original source material to create what is essentially a new story. A good movie is not always a good adaptation, but good adaptation should on some level be a good movie.

Where this kind of adaptation can tend to go bad is when the original source material is both being twisted to meet the needs of the external motivation, and is relied upon to serve as the frame of an otherwise incomplete work. You can just write an action movie for teenagers about a sexy vampire, but for it to be successful it needs to be interesting enough for you to market it and for it to have its own core appeals. If you can’t make a real story with its own appeal, you can instead rely on an existing intellectual property that already has marketable value, and use the pieces of it to assemble into something that looks enough like a real movie that you can convince people to watch it regardless of whether or not it works as a film.

If Queen of the Damned was a bad adaptation of the novel The Queen of the Damned while being a good movie, I would put it under the umbrella of things like the musical Wicked where the derivative work has enough appeal in itself that losing the core elements of the appeal of the original would not affect its quality as its own work. However, because it's not a good movie, I find it's adaptational choices much more frustrating. Obviously, people enjoy movies subjectively, but from an actual structural standpoint where characters act consistently in a screenplay and events logically follow each other and create an emotional effect in the audience, the movie Queen of the Damned is not a functional film. What happens in the movie and what the characters do feels completely random, because the choices made in the adaptation are not centralized around a guiding principle that determines what to maintain and what to discard.

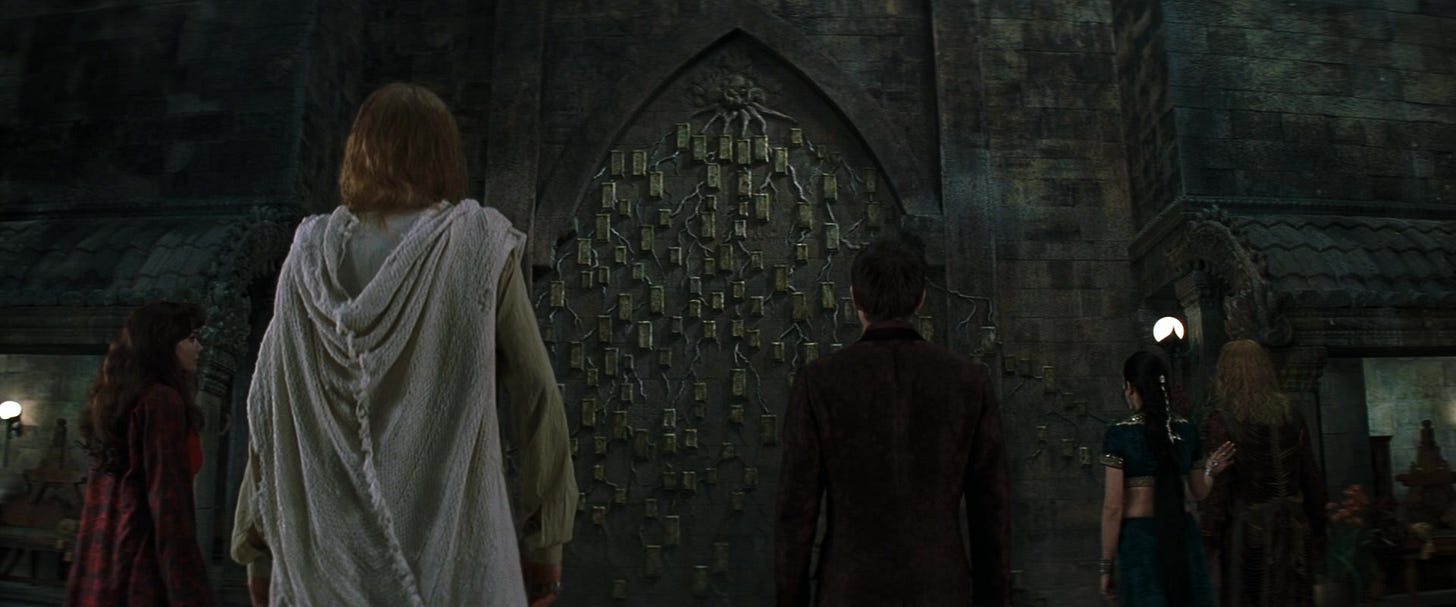

The climax of the movie Queen of the Damned starts when the vampires stand around a family tree, and after discussing it, resolve that humanity is worth saving. The reason why this is the finale of the movie Queen of the Damned is because it is the finale of the book. That is in fact how the climactic scene of the novel The Queen of the Damned starts. However, the pieces that make that scene a key element of the climax of The Queen of the Damned are not in the movie, so the fact that the vampires decide to save humanity by looking at a family tree becomes a complete non sequitur. The vampires in the room have not been well established as characters, to the point that many of them don't have names in the theatrical cut of the film and most of them don't have any dialogue. Who the family tree is of is not particularly well established and the person describing the family tree is so poorly established that she is only in one or two scenes prior to this one. The thematic and emotional reason why this is a culmination of the story we have been watching has not been established because the themes of the movie are vague, nonspecific, and don't include the reasons why this should matter. Not changing the reason why the vampires decide to save humanity is a bad adaptational choice, because the choices that were already made to turn the story into a vampire action movie for teenagers have already necessarily removed any context in which it makes sense.

An adaptation is not bad because it changes too much from the original material or changes specific elements of the original material. An adaptation is bad when it doesn't have or fails to stick to a central guiding principle in what it decides to include, cut, or change from the original work.

Stuart Townsend is not my Lestat, because he is not playing a coherent character. So many elements of the character have had to change to force the story into the Underworld shaped box it is in, that the main vampire character is doing fifteen contradictory things, none of which happen to be being Lestat.

Part Five: Why adapt something if you're going to change it?

I was not a fan of the Vampire Chronicles at the time that the AMC adaptation of the book Interview with the Vampire was announced, but from what I know fans of the series were not optimistic about it because of the substantial and fundamental changes to the original story that they already knew from day one were going to be made. The first and biggest change in the adaptation is that the timeline is substantially different, the events of the story being shifted from taking place in the early 1800s to the early 1900s, and an almost equally large change was made to the protagonist of the novel, Louis, who is a white French plantation owner in the original. In the adaptation, Louis is instead a man of color descended from a similar type of plantation owner, and rather than profiting from the labor of enslaved people of color, he is profiting from the sexual labor of women as a pimp.

Reading some of these negative fan reactions now, they tend to fall into two camps, one I am sympathetic to and one I have absolutely no sympathy for. As I mentioned, one of the features of Interview with the Vampire and the Vampire Chronicles more generally that can be a primary appeal to a lot of readers is the setting and the time period, and so changing the timeline of the series for readers who really enjoy the time period and setting of the original book implies that the series is deprioritizing elements that are part of their own emotional interaction with the work. That, I am sympathetic to, especially when the work has not yet been released and you are imagining based on limited information how they are going to prioritize different elements of what appealed to you about the original, knowing only that they have already decided to change one of them. What I am not at all sympathetic to is people who strongly reacted to the racial change of the main character, many of whom tried to justify it as being a fundamental feature of the original work that could not be changed in adaptation. If the appeal of a work to you is not present in an adaptation of that work because a character is not white, you should examine why. If your emotional relationship with a narrative is no longer possible if the sympathetic protagonist of that narrative is not white, you should probably think a little bit harder about why you feel that way, especially if what you are reacting to is a hypothetical adaptation that has not been released yet based on a casting announcement.

When the AMC show came out, I had already seen the original 1994 movie and Queen of the Damned, and neither of those adaptations had connected with me enough for me to seek out more information about the source material. I don't like nu metal music, vampire action movies as a genre have very little to offer me to the extent that it's a running joke I make about myself, and when it comes to 1994's Interview with the Vampire, even though I can understand the reasons why other people enjoy it, there was nothing in it that really connected with my personal taste. I decided I was going to eventually read the books after watching season one of AMC's Interview with the Vampire, and I desperately sought out and started devouring the books halfway through season two.

As a reminder, here are the primarily appeals as I see of the Vampire Chronicles for readers: the philosophical discussions, the themes around the search for morality and purpose, the well-defined characters and their dynamics with each other, the historical fiction elements and the scope of the timeline, the haunting and evocative horror scenes, the touches of black humor and absurdism, and the extremely distinctive lush gothic mood in the writing style.

The reason my entry into the Vampire Chronicles came from the AMC show is because the AMC show’s central guiding principle it chose from the many possible appealing elements of the books were the dynamics between the characters and how those dynamics utilized to construct the larger themes of the story. Every other choice made in the adaptation, even some of the biggest departures, are based around the idea that telling the story of the interpersonal dynamics between immortal characters allows you to create larger than life metaphors and discussions of bigger ideas in a fantasy context. That is the core and most important idea guiding this particular adaptation, and now that I have read the books, I understand that this is the first adaptation I have been a huge fan of because that is the part of the story of the books that I find most appealing. I did not know that was a feature of the series from the prior adaptations; once I knew it was, I was able to form my own emotional relationship with the book series and its other appealing elements from that starting point.

Now having read the books, I can see the ways in which my emotional relationship with that particular element of the books and the ways it was adapted into the series are not exactly the same. The biggest reason why is because the show is using the style of how the book uses these character dynamics to discuss greater things to discuss different themes and ideas than the ones discussed in the books, and some of the major themes discussed in the books are extremely specifically emotionally resonant with me in this particular season in my life in a way the themes of the show don't happen to be. Is it therefore a bad adaptation to me now? Is this not my Lestat in the same way that Tom Cruise is not my Lestat? Not really.

When you are making an adaptation of a work, because we live in a world where things cost money and there are finite resources, there needs to be some reason why you are doing that, and if you're adapting a work for the second time, you need a pretty decent reason why. The original 1994 Interview with the Vampire is not by any standard a bad adaptation or a bad movie, so if you are going to make it again you need to come up with a reason why retelling this story is important enough for us to watch it. You can read Louis complaining about his life, you can watch him complain about his life in a movie, and you can even listen to him sing and watch a bootleg stage performance of him complaining about his life, but if we are going to make another version of that story, the translation between mediums is no longer a justification for why it's being made. Something else needs to matter about the new work you are making.

One argument I could see someone make for why there is a reason for a faithful television adaptation of Interview with the Vampire to be made is because television shows have more time to adapt their source material than a movie does. I think is a weak argument if the original adaptation was successful. At this time, HBO is apparently still going forward with their plans to make new adaptations of the Harry Potter books as a television show, and I, regardless of any other factors that play into my current feelings about Harry Potter, cannot care about it because the original Harry Potter movie franchise is a very successful and well-made adaptation of the books. There is extraordinarily little gain from a new television adaptation of a book that was already well-adapted into a movie if the only guiding principle of the new adaptation is to include things that had to be cut for time. Even though the translation of the way the characters operate in the original Interview with the Vampire movie does not personally work for me, a new adaptation that uses itself only as an opportunity to correct that element is not worth it when the original movie is as good as it is. There is nothing about that movie that can be improved to the point of justifying an additional adaptation by simply adding more minutes to the time it takes to tell the story.

What the showrunner decided to do was to take the elements that were the core appeal of the original work of Interview with the Vampire, and adapt them in such a way that they can be synthesized and merged with a focus on new elements consistent with the existing elements of, but not a already in, in the original work, enhancing both by creating new meaning from the original work and by framing these original ideas within the excellent elements already present in the source material.

This next part is going to seem extremely flippant, but I mean it sincerely: A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is a great story, it is a complete and important narrative about the value of family and community, and when you add puppets to it, you enhance the themes about family and community by making it accessible to children, and you enhance the puppets by giving them a strong narrative for their humor to be structured by. The reason the television adaptation of Interview with the Vampire is good is the exact same reason why The Muppet Christmas Carol is good. It takes the strongest elements of the original work and merges them with new elements that are relevant to the target audience in such a way that both the new elements and the original elements are made better. A Christmas Carol was already intended provide moral lessons to adults and children, so adding an original element that makes it more appealing to children specifically is enhancing the original instead of departing from it. Adding the element of explicit queerness and discussions of race to a story about the experience of the outcast does not replace or remove the original elements of that story, it enhances them by making them more relevant to the time period in which the adaptation is being made, and allows a new work to say new things and hold its own appeal.

Would I prefer a perfect adaptation of Interview with the Vampire to the AMC adaptation if they were both of the exact same quality? No, because perfect adaptations of things do not exist, because of everything I have said up until this point. Even a very good adaptation will not be perfect, and so merging what appealed to audiences about the original work with new elements with their own compatible appeal is going to make the result itself a better complete work while also working better as an adaptation.

Sam Reid is not my Lestat because my Lestat lives in my brain and is the result of my own imagination and the imagination of Anne Rice making a baby who is a character I have a personal emotional relationship with. Sam Reid is a human actor playing a character on a television show about the complex interactions between queerness and race and trauma, and I think he does a great job translating the elements of the character that are important to mine and many other readers’ emotional journey with that character into this story. He has to make concrete choices, but he is making them while being aware of what the central appeals of the character are, and so even when he is not my Lestat, he is still my favorite Lestat who has existed outside of the novels and my head.

Part Six: Adaptations are Scary

When I think about the fact that season three of AMC's Interview with the Vampire is going to be the third adaptation we've seen of an audio-visual translation of that novel (it was included in both Lestat the Musical and Queen of the Damned), I am very nervous. Even though I read it for the first time only four months ago, I have already reread the novel The Vampire Lestat and have reread specific chapters about ten times. The emotional relationship that I have with this book is intensely important to me as a person, and because of that, I am nervous about the adaptation being able to live up to how that book makes me feel.

You never get to experience a work completely fresh a second time. You never get the exact same feelings you had as you watched the story unfold before you. Reading a book a second or third time has its own appeal, but often when we are talking about adaptations of a book that is important to us, what we are looking for is on some level getting to experience that feeling that was reading it for the first time. You can read a novel for the first time and go on an emotional journey, and you can watch a movie for the first time and go on an emotional journey, and when something important to us is adapted we really want those emotional journeys to feel comparable. We expect that they will be and feel as though we have been wronged when they are not.

I'm a big re-reader and a re-watcher, and I think accepting that an adaptation of something you love does not have to recreate the emotional experience you had with the original is accepting the appeal of returning to the same stories over and over again. I'll never experience the absolute stab to the chest that was reading The Vampire Lestat for the first time again, but rereading it is not an attempt to have that feeling again, it's an attempt to dive deeper into it and understand something deeper about myself and about the book that created that feeling. Returning to the same works over and over again can be a second journey, or it can be a return to comfort when the elements of what appealed to you and allowed you to form that emotional relationship are there to be explored over and over in different ways. Your relationship with a text is the first emotional journey you went on with it, but it can also be every single other emotional journey you've been on with it since, whether it was when you reread it, or when you saw the movie adaptation, or when you read some fan analysis of an element you never thought about before. Even though it feels like we want the path again that we already went down, what we really want is to explore all the little side streets, we want to get lost down the alleyways, we want to stop and spend more time looking at that one cool thing or adjust the angle we're looking at it from. Being a fan of something, having a work that is important to you, is not a static experience. It's always dynamic.

When I watch a movie based on a book I like, I should not expect that I will feel the same way I did the first time or the second time or the fiftieth time I read the book. The book and the journey it takes me on is the book’s journey, and the movie or the TV show and I will have our own. That does not mean the quality of an adaptation is meaningless, because we live in a world with finite resources where the minutes I spend matter to me and what studios decide to spend their money making impacts what I am able to watch, but it does mean that I do not need to like adaptations in the exact same way that I like their original source material for them to have value. They are another way in which I can engage with the elements of a story that meant something to me, and if they are good, they can give me new ways to find meaning in those elements.

If an adaptation of The Vampire Lestat can be a tenth as special to me as the book was, it will be a really damn good work, but it will still not be the novel The Vampire Lestat. I hope I get a really good, really affecting, beautiful television season that leads me through an emotional journey of the relationships of the characters, experience the themes of the novel and some of the philosophical ideas in it, and I also hope it has great television production and that the episode breaks are great cliffhangers, and that the places where the writers and I don't agree on what's appealing are still interesting enough that I don't mind.

It will never be my The Vampire Lestat. I just hope, so much, that it will be the best version of The Vampire Lestat that can exist outside of the novels and my own head.